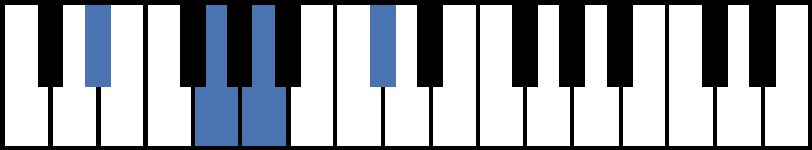

The issue is that if you start on C and tune four mathematically pure fifths in a row upwards, the resulting E will be exceedingly discordant (C→G, G→D, D→A, and A→E). However, in the late medieval/early Renaissance period, musical tastes shifted, and the third interval became popular. Pythagorean was the most popular tuning in the early medieval period, in which fifths are mathematically pure. We don’t notice this since we’ve heard equal temperament keyboard instruments since we were children. However, most equal temperament intervals are far from mathematically pure.

We tune most current organs and pianos under an equal temperament method, which divides the octave evenly into 12 distinct pitches or semitones. Since introducing the keyboard, instrument builders, composers, and theorists have wrestled with precisely how to split an octave interval. When E Flat and D Sharp Are Different NotesĮthan Hein explains why D♯ and E♭ are distinct notes in this thorough analysis. Other times, especially in more modern music where no key signatures are used, a composer may choose to present either D♯ or E♭ depending on the overall context of the music. Other times, composers will also use D♯ instead of E♭ as a courtesy to musicians to make reading the music more accessible. You can watch an example in the video to see how Brahms used enharmonic spelling to lead the music back to B minor. If you read a piece in B major, you will expect to see a D♯ in E minor, you’ll also expect a D♯ because it is the raised seventh step of the scale.īut, sometimes, a composer will break the accepted rules and use enharmonically spelled notes for a particular function. We can illustrate the point below: Correct and incorrect ways of spelling a B major scale ( source)Īs you can see, reading a B major scale written with flats is quite challenging but not impossible. You’ll probably also lose marks on a theory exam. If you were to spell it as B♮, D♭, E♭, E♮, G♭, A♭, B♭, B♮, it would sound the same, but it is a lot harder to read and doesn’t make ‘sense’ within the established rules of Western music theory. Suppose you spell a B major scale the following way: B, C♯, D♯, E, F♯, G♯, A♯, B. But, because we can write notes with different names doesn’t mean we should do it for the fun of it. When you spell a note enharmonically, that is the same note spelled differently.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)